So, uh…how about that dang ol’ 2020, huh?

A lot has happened in the world since I last wrote you, Terrorteers, on both a macro (a deadly pandemic, a rapid slide into a dystopian police state, murder hornets) and micro level (friendships and relationships coming and going, moving across the country, career changes), but there’s also been something of a shake-up in the world of Terror High as well: We’re changing engines.

When I started development in October of 2018, I was using Clickteam Fusion 2.5, the latest iteration in Clickteam’s series of script-free programming tools that first started with Klik & Play.

I first discovered Klik & Play as a young teen via its signature splash screen at the end of a South Park dodgeball fan game and immediately had to buy (or beg my mom to buy) it. I think at the time it cost, like, six bucks, and came on a floppy disk. Looking back, it was remarkably primitive, but it opened the door for me to start getting my hands dirty with all of the game ideas I’d had floating around in my head (or scribbled down in notebooks) for years.

I stuck with Clickteam for the next two decades through each of their subsequent iterations, up to the DLC for Clickteam Fusion 2.5 (which added a jaunty plus sign to its title as well as a handful of sorely needed features and expansions). But while Clickteam’s software is a wonderful introduction to game creation and its community (such a foundational part of my youth, in a way that’s hard to explain unless you also grew up with it) (gosh, I miss the wonderful jank of late ’90s/early ’00s internet) has produced many wonderful titles, my ambitions, always outsized, quickly began to push at the edges that Clickteam’s box had it in. It grew harder and harder to wrestle its engine into doing what I wanted, but for the longest time there was a sunk cost fallacy in how much time I’d spent with it and neglected learning “real code”, and a misguided idea of myself as an “art person” and not a “code person”.

Eventually, I realized that the amount of increasingly-complicated workarounds and problem-solving I was forced into with Clickteam Fusion 2.5 disproved that notion, and I was, in fact, perfectly capable of being a “code person” if I just sat down and learned some syntax. I also realized that if I was already running into these limitations this early in the process, before major content had even begun to be implemented, I might be using the wrong tool for the job.

And thus, I found myself in Unity’s warm embrace.

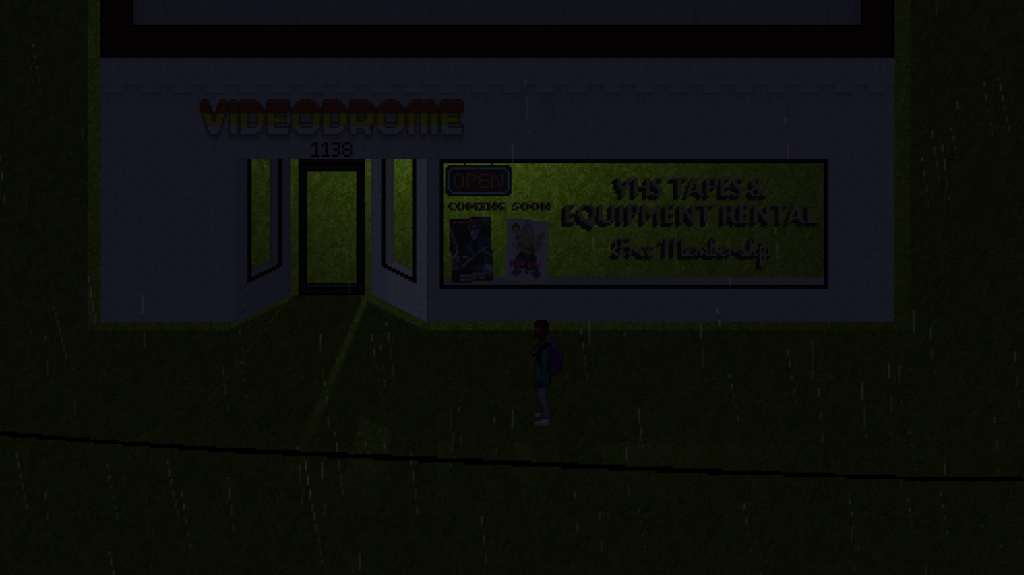

I set out to learn C# and Unity back in April, and I’m taking to both rather well. It will take me a while to learn all the ropes and get Terror High up to where it was in Clickteam Fusion 2.5, but I’m confident this is the right move for the game and for me as a creator. It’s already allowing me to achieve lighting effects I could only dream about in CF2.5:

This change in engine is not without its irony, though. With CF2.5, I was struggling to recreate 3D effects in a 2D engine. With Unity, the struggle is recreating a 2D aesthetic in a 3D engine. Luckily, others have trod this path before so that we might learn from them.

In Enter the Gungeon, the developers faced this same dilemma. Their solution was remarkably simple, and takes advantage of the orthographic camera and some simple maths to fake that perspective that we know and love.

The game world exists on a 45 degree angle, with upright sprites angled 45 degrees toward the camera, and ground sprites angled 45 degrees away.

Because of this angling, however, art appears squished:

To account for this, everything is then scaled by square root (2) along the Y-axis, et voila:

The assets themselves have also had to go through an upgrade to find their way in this new dimension. I originally tried to piece together buildings out of separate sprites, but the sprites’ lack of depth lead to Olestra-levels of leakage, with lights failing to be blocked by sprite walls:

This dilemma lead me further down the dimensional rabbit-hole, where I eventually decided the most sensible way to get a building to have three dimensions would be to, well, build it in 3D. But I still wanted them to retain the look and feel of their 2D origins, which were designed with 2D tiles in mind. What’s a fella to do?

My research led me to Sprytile, a wonderful, free plugin for Blender that makes it easier and more intuitive to build 3D models out of 2D tilemaps. It has its quirks in Blender 2.8, but so far it’s been a pleasure to work with, and has allowed me to translate my 2D designs into the 3D world far easier than I was able to do in my pre-Sprytile attempts.

There’s one other issue with this transition to 3D that I haven’t quite figured out how to deal with yet, and that’s sprites’ complete lack of depth on the X-axis.

I’m still not quite sure how, or if, I’m going to get around this flaw. I could maybe have copies of the shadowcasting sprite that billboard in the direction of the light, or a hidden 3D shadowcaster to provide the needed depth. Or maybe I just won’t worry about it. Maybe players won’t mind. Maybe nobody minds about things as much as me.

2020 has thrown us a lot of curveballs, and I’m sure 2021 will be no different. But despite the chaos and uncertainty, or maybe even because of them, I’m still working, still creating. Until next time, Terrorteers, as we wait for the Great Leap Forwards: Be excellent to each other, and party on, dudes.

But, you know, like, over Zoom and in your hearts and stuff. Not, like, in person.